Throughout human history, the ownership and control of land have symbolized not just wealth, but also power and authority. In ancient times and feudal societies, land was not merely property—it was the foundation of governance, military strength, and social hierarchy. One of the most significant concepts in traditional political systems was that “all land belongs to the king.” This idea underpinned various civilizations across the globe, from Europe and China to India and the old Siamese kingdom.

Royal Ownership and Feudal Hierarchies

In many civilizations, kings and emperors claimed divine or absolute ownership of all the land within their realms. The people, in turn, could only use the land if granted permission, often in the form of royal charters, leases, or feudal contracts. In medieval Europe, for example, feudalism structured society into hierarchical layers, where kings distributed land to nobles in exchange for military service and loyalty. These nobles, in turn, allowed peasants to work the land, collecting a portion of their crops or labor as tax.

Similarly, in imperial China, the emperor was seen as the “Son of Heaven” and held supreme authority over all territory. Even when citizens had long-term use of land, they remained obligated to pay taxes and acknowledge the emperor’s ultimate ownership. Land was both a spiritual and political asset.

Siam (Thailand) and the Royal Land System

In old Siam, the belief that “all land belongs to the king” was embedded in the sakdina system—a socio-political structure based on rank and land allocation. Under this system, the monarch had absolute power over land distribution, and nobles received land and laborers based on their official ranks. Land measurement and taxation were tied to manpower, and people’s roles in society were closely associated with the land they cultivated.

The state’s ability to levy taxes and maintain control depended on the centralized power of the monarch. However, this structure gradually began to shift with the advent of modernization, capitalism, and political reform.

The Turning Point: Land and Power in the Age of Revolution

The French Revolution of 1789 marked a monumental turning point in the history of land ownership and political power. The revolution dismantled feudal privileges and royal land control, promoting the idea that sovereignty belonged not to the monarch but to the people. Land reform, abolition of noble estates, and public taxation systems reshaped Europe’s economic and political structures.

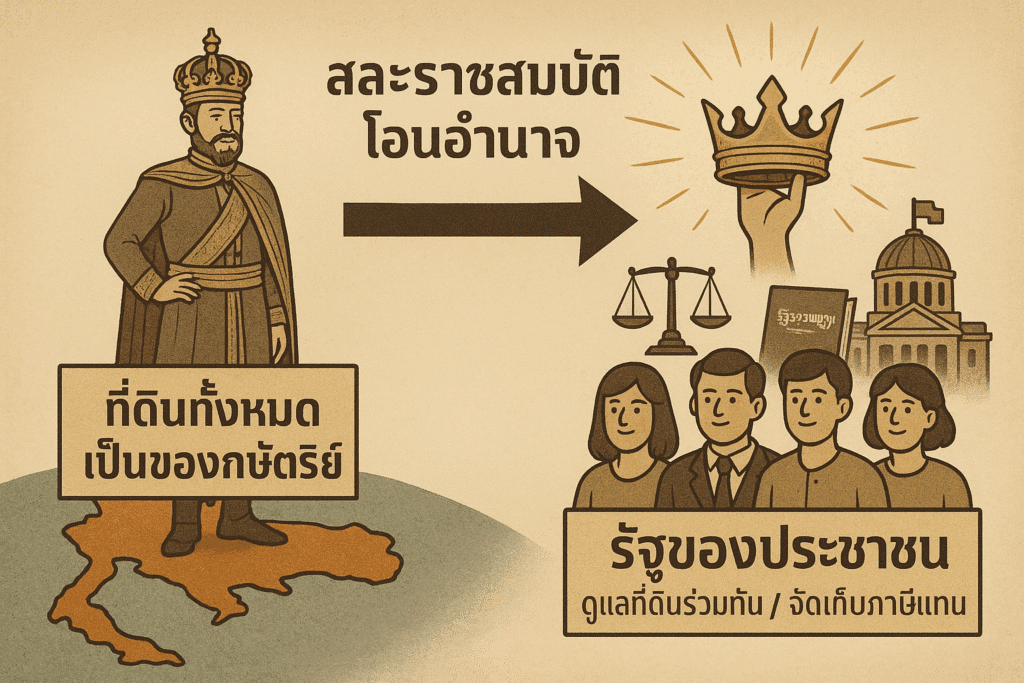

This revolutionary idea—that the state exists to serve the people, not the monarchy—soon spread across continents. It ushered in the era of nation-states, where governments, elected by the people, assumed responsibility for managing land and collecting taxes for public benefit. Kings no longer ruled by divine right; instead, legitimacy came from the will of the people.

The Thai Transition: From Monarchy to Constitutional State

In Thailand, the process of transformation began during the reign of King Rama V (Chulalongkorn), who initiated major reforms to modernize the kingdom. The abolition of slavery and the restructuring of the bureaucracy laid the groundwork for a more inclusive society.

The real political shift came in 1932, when a peaceful revolution changed Thailand’s system of governance from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. While the monarchy remained deeply respected and continued to play a symbolic and spiritual role, the actual management of land and taxation was transferred to the state—a body meant to represent the people’s collective interests.

The idea that “land belongs to the king” evolved into a modern interpretation where land is managed by the state for the benefit of the nation, under laws enacted by representatives of the people. Today, land ownership in Thailand is governed by a legal framework that ensures private rights, while the government retains authority to manage land use and taxation.

Modern Governance: The State as Steward

In the contemporary world, the state has replaced the monarch as the primary steward of land and national resources. Through legislation, land registration, and property tax systems, governments exercise their authority not as monarchs, but as administrators accountable to the people.

Taxation—once a symbol of royal authority—is now a mechanism for democratic governments to generate revenue for public services, infrastructure, education, and healthcare. The shift from royal power to public governance reflects a deeper philosophical evolution: power no longer flows from a throne, but from the collective voice of the people.

The Symbolism of Transition

This historical transition is more than legal or political—it is symbolic. When a king “relinquishes” land to the people, it signifies the end of a top-down power structure and the birth of mutual responsibility. The people do not merely “own” the land; they become guardians of it. The state, acting on their behalf, must govern justly, collect taxes fairly, and ensure that land is used sustainably and equitably.

This also changes the way citizens relate to the land. Instead of being tenants of a king, they are now stakeholders in a shared national project. Citizenship replaces servitude. Representation replaces decree.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Shared Responsibility

From ancient kingdoms to modern democratic states, the relationship between land, power, and taxation has undergone profound transformation. What once was the divine right of monarchs is now a shared responsibility between the state and its citizens.

Land remains central to human society—not just as an economic asset but as a symbol of belonging, identity, and power. Its evolution from royal possession to collective stewardship is a testament to the enduring quest for justice, equality, and participation.

As nations continue to evolve, the legacy of this transition reminds us that while power may change hands, the duty to protect and use land wisely endures in every generation.